The following is a clip from the advocacy chapter of The Late Talker book which is highly recommended

The following is a clip from the advocacy chapter of The Late Talker book which is highly recommended

Chapter 6. GETTING THE ANSWERS THAT YOU NEED

As a parent of a non-speaking child it is up to you to be their voice.

—KAREN D. ROTHWEILER

Mother of three-year-old Justin

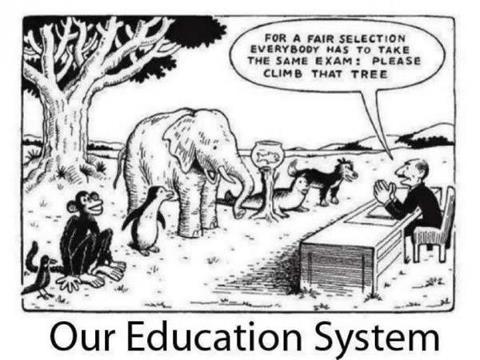

Know your rights. Know your child’s rights. One of the greatest challenges faced by parents of children with speech delays is making sure that their kids get the assistance they deserve. Parents often find they have to fight their way through a bureaucratic maze on at least two fronts. On the one hand, they may encounter an educational system that’s not geared to meet the needs of a non-verbal child. On the other hand, they may find that their health insurance company refuses to pay for the intensive therapy these children must have. You may have to be tenacious. You may have to fight tooth and nail. You may have to learn more than you care to know about the minutiae of the law. But it’s your child and if you’re not going to be his number one advocate, who will?

In this chapter, we give you an essential step-by-step guide: how to acquire early intervention (EI), how to handle the school system, and how to overcome insurance company roadblocks. While much of this information is useful for parents of children with speech delays it is absolutely essential reading for parents of children with apraxia and other moderate to severe speech disorders. Let’s start with education. Under the law, your child is entitled to a “free and appropriate public education” (FAPE). The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) guarantees a public education to every child, aged three through twenty-one, in need of special education services. Public schools must provide services in the “least restrictive environment,” and must create and implement an Individualized Education Program (IEP), specifically designed to meet each child’s needs. This program is usually called a “preschool disabled program.”

In addition to the educational component, the IEP must include “related services” such as speech, physical, and occupational therapies. It also covers the provision of transportation, augmentative communication devices, and counseling services. As the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, puts it: “Each IEP must be designed for one student and must be a truly individualized document…The IEP is the cornerstone of a quality education for each child with a disability.” Amendments to IDEA, passed in 1986, extended the legislation to provide early intervention (EI) services for children from birth through the age of three.

Early Intervention

If your child is under the age of three and you’re concerned about his development, obtain an evaluation through your local early intervention program. Any child suspected of having a delay in any aspect of his development is entitled to an evaluation to see if he is entitled to special education services. To be eligible for services children must have a disability or established delay in physical, cognitive, communication, social-emotional, or self-help development. For the purposes of EI, a developmental delay is documented as a 33 percent delay in one area of development or a 25 percent delay in each of two areas of development. For example, a twenty-four-month-old month toddler would qualify for services if he was functioning at the sixteen-month level in communication ability, or at an eighteen-month level in both communication and physical (motor) areas. EI, also known as the Birth to Three program, is a family-centered program. Parental consent is required for an evaluation and parents are part of the process in establishing goals and monitoring outcomes of treatment. In some states, the program is free of charge; in other states, there may be a sliding scale of costs depending upon parents’ income.

Unfortunately, many children with speech disorders never have the opportunity to benefit from early intervention because their parents listen to the standard advice to “wait until he’s a little older.” Our advice: contact EI as soon as you’re seriously concerned about your child’s ability to communicate. There is no age that’s too young for referral to EI. The Clinical Clues chart in chapter one gives guidance on appropriate warning signs. (Quite often, preschool teachers or daycare personnel alert parents if they suspect a problem). Ask your pediatrician for a referral, or call EI yourself. You can find your state’s EI coordinator through the National Childhood Technical Assistance System (NECTAS): or your local Department of Health.

Early Intervention services are usually provided in “natural environments” which may be the child’s home, the day care center, or the playground. Services vary from state-to-state, but no matter where you live the initial evaluation will probably be conducted in your own home. Although your entire focus might be on your child’s speech delay, EI programs perform a full multidisciplinary evaluation. The professionals test your child’s ability to communicate, and perform gross and fine motor tasks as well as evaluating cognitive, self-help, and social, behavioral and emotional skills.

Should your child not qualify for services, question how the speech and language assessment tests were scored. Make sure that the evaluator did not average the receptive and expressive language scores. It’s quite possible that your child has age-appropriate auditory comprehension (receptive language), but significant speech and expressive language delays. Averaging the scores artificially inflates the overall communication score and could disqualify your non-verbal child from EI services. For example, if your thirty-six-month-old’s receptive language is typical for his age, but he has a twelve month delay in expressive language, the average of the two scores (thirty six and twenty-four) brings him to thirty months, which may disqualify him from services. Should services be declined you have the option of getting a second opinion from a private therapist. If you cannot obtain free EI services and you feel that your child needs therapy you would have to obtain this through medical insurance or pay privately. If cost is an issue, approach subsidized programs such as Easter Seals or Scottish Rite or check out clinics at teaching hospitals or universities as they may offer services at reduced fees.

After the EI evaluation, the multidisciplinary team writes a report about your child’s developmental status. If your child is found eligible for services, your service coordinator, a member of the evaluation team, an EI representative (Early Intervention Official Designee – EIOD) and you meet to develop an Individual Family Service Plan (IFSP), which describes your concerns, priorities, resources and desired outcomes for your child. States vary with regard to the extent of delay that warrants EI services and the amount of therapy they provide. Typically, you can expect to get two hours of therapy a week, which is not enough for a child later diagnosed as apraxic. If that’s all you can obtain, ask for it to be divided over four days as more frequent, shorter sessions are best for apraxics.

Because it has been designed by experts, is based on solid research and fully involves families, EI stands a good chance of enhancing the child’s development and improving his chances of educational success. If you disagree with the findings of your child’s evaluation team or the IFSP, in most states you can request a second evaluation or exercise your right to mediation or an impartial hearing.

Plan Ahead

When your child is three years old, whether he was in Early Intervention from the state or not, he may qualify to enter the school system’s Individualized Education Program (IEP) in which you and a team of experts agree on the quantity and quality of services he will receive. This is an essential right and key to ensuring that he receives at no cost the kind of education that he specifically needs. But don’t wait until his third birthday before requesting services. When he’s two-and-a-half call your school district and request an evaluation. This way you won’t miss a day of services. If he’s been receiving therapy through EI, they can help with the transition. As with the IFSP, special education laws vary from state to state. The U.S. Department of Education has a fifty-page “Guide to the Individualized Education Program” which emphasizes that the creation of an effective and unique IEP requires parents, teachers, school administrators and specialists working together as a team. It can be downloaded here

We Are the Parents (Poem) by Kay Kronquist

Dealing with IEPs for a Speech Impaired Child (Information from Lisa Geng and the Cherab Foundation)

If your town’s school is in the US than it receives Federal monies and has to by law follow the Federal (not just State or City) laws. The Federal Law is FAPE in the LRE or your child is entitled to a free and appropriate public education in the least restrictive environment and you’d be shocked how much is offered once you learn how to advocate.

If your child doesn’t yet have a diagnosis it’s highly recommended to seek one. The IEP will typically state the diagnosis if the parent supplies it to them. Schools will not diagnose -they will tell you if there is a receptive or expressive delay etc. and let you know if your child qualifies for services through the IEP. Children are entitled by Federal law to a Free and Appropriate Public Education in the Least Restrictive Environment and this starts with the preschool program… from what you are saying your child does not qualify. Many children in our group have expressive delays -but that doesn’t mean receptive delays and yet without advocacy and appropriate testing the word “receptive” delay frequently will be added to the IEP too. This again is why an outside evaluation is highly recommended.

If you don’t have a diagnosis, you really want to know the reason for your child’s delay in speech as there are quite a list of reasons. Here are questions to get started on your road to advocacy.

- Who evaluated your child thus far?

- What is your child’s diagnosis?

- Have you observed the therapy at school to see how knowledgeable the therapist is about your child’s condition?

- Do you believe you would be able to tell the difference?

- Do you have any local support groups near you to have someone who has been there before help you advocate?

- Since school began are you noticing any improvements with the therapy?

- What do the IEP goals have for 3 months -6 months goals?

It’s best for your child for you to know by a neurodevelopmental medical exam (pediatric neurologist or neurodevelopmental pediatrician if apraxia is suspected) if there are signs of sensory integration dysfunction or hypotonia and/or motor planning issues so that you can secure appropriate therapy for these co existing conditions as well in the IEP. Of course, in addition to the neuroMD exam, it’s best to secure an outside the school SLP/ outside the school OT as well. Another reason for a diagnosis is because without one they may write into the IEP there is a language/receptive delay. That may be inappropriate as the signs of a receptive delay may be due to an impairment in speech and or motor, sensory or weakness issues.

Here is an appropriate way to test a child with a speech impairment

Summary of assessment procedures Children with significant language and motor skills delays by Robert E. Friedle, Ph.D. Clinical/Neuropsychologist

Formalized assessment of children with low incidence disabilities does not often provide accurate or practical information about their cognitive functioning skills. Such assessment does provide evidence that these children often have not learned how to respond in direct one-to-one reciprocal testing situations, or that they are unable to respond in those situations due to the nature of their disabilities. The lack of response should not be considered then, necessarily, as a global and fixed delay in cognitive/intellectual potential. Developmental theorists and practitioners have long known that cognitive growth is not only enhanced but also dependent upon opportunities to experience a wide variety of sensory stimuli in an interactive relationship. Problem-solving skills, analytical reasoning, and decision-making are all formalized, cognitively, when the integration of information is ongoing. Language and motor skill limitations often prevent the integration and experiences and thus certain cognitive growth waits until such experiences may be provided.

Formalized assessment of children with low incidence disabilities does not often provide accurate or practical information about their cognitive functioning skills. Such assessment does provide evidence that these children often have not learned how to respond in direct one-to-one reciprocal testing situations, or that they are unable to respond in those situations due to the nature of their disabilities. The lack of response should not be considered then, necessarily, as a global and fixed delay in cognitive/intellectual potential. Developmental theorists and practitioners have long known that cognitive growth is not only enhanced but also dependent upon opportunities to experience a wide variety of sensory stimuli in an interactive relationship. Problem-solving skills, analytical reasoning, and decision-making are all formalized, cognitively, when the integration of information is ongoing. Language and motor skill limitations often prevent the integration and experiences and thus certain cognitive growth waits until such experiences may be provided.

Children may have learned to problem-solve and reason in ways that are not assessed by formalized evaluations and are only recognizable when the child is allowed to experience sensory information in a manner most productive to them. It is often than necessary for the examiner to assess what opportunities and experiences the child may have had already, how an assessment may prompt the child to show what they can do with various stimuli and how problem-solving, analytical, and decision making skills can be exhibited by a child in a non-formalized approach.

The purpose of an assessment request has to be relevant to the child and to their experiences, i.e. the child needs to see some purpose for providing a response. A very simple example of this premise is: asking them to name an object may result in no response, but asking them to get the object may show a knowledgeable response.

Children with language and motor deficits often play within the restrictions that their limitations have presented and this “changed” pattern of play, from what is seen with non-disabled children, can be a direct reflection of their ability to problem solve and reason in play. An example for this may be when a child finds that laying things down and flat makes it easier to manipulate, or that moving things closer or out of the way facilitates motor planning and play. Often the child may see no purpose to expand experiences, or have not figured out independently how to change their play patterns.

Restrictions in movement or language limit the experiences a child has had with objects and stimuli. The need to practice simple movements, to hear the words that go along with those movements, and then to ask a child to duplicate the movements and/or the words can greatly facilitate cognitive growth. If a child can readily make such duplicated responses then the potential for cognitive growth at that point presents no limitations. An examiner can lead the play situation in these types of activities and note the ability of the child to engage in the “play” at a different level. The purpose is then presented clearly for the child, both for the language and for the movement, and thus becomes an active part of their developmental growth and understanding. Sometimes showing them or asking them to change their approach results in a larger perspective of possibilities in play. The examiner is an active participant in the assessment approach, engaged with the child in the semi-directed play type of assessment. The examiner notes closely when a child shows a lack of understanding of the language presented or an inability to make the movements requested. At all times the examiner is assessing how well the child appears to follow the purpose of the activity or the change in direction of an activity.”

With or without a diagnosis however you can still use the severity intervention matrix guide used by the schools to determine how much therapy a week is needed based on severity.

And as it says at the bottom CHERAB and The Late Talker book were both granted permission to reprint this: “By the age of 7 years, the student’s phonetic inventory is completed and stabilized. (Hodson, 1991). Adverse impact on the student’s educational performance must be documented. If the collaborative consultation model of intervention is indicated at the meeting, the student receives one additional service delivery unit.”

Source: Illinois State Board of Education (1993). Speech-language impairment: A technical assistance manual Springfield: Author: Reprinted by permission. (permission granted 11/28/2001)

You want short as well as long-term goals because after 3 months if there is no progress either the therapy, therapist or diagnosis should be examined again as perhaps one of them isn’t appropriate. It’s a bit of a time game in that your job is to help get your child up to speed as quickly as possible and not to keep them in a situation just because he’s getting the right amount of the wrong therapy or the wrong amount of the right therapy. Don’t worry about hurting anyone’s feelings because in a year or so you may never see the same school professionals again, you could move, but your child is always your child.

A note of advice when dealing with the IEP team

You want to make sure that the words “best practice” are in the IEP and not the words “best method”. If you say “best method” the team realizes that they are dealing with someone that thinks they know all that child needs and it drives the team crazy. Best practice means we have to try this and see if this works and if it doesn’t we can try something else. Method limits you but practice opens it up to try different strategies until you find a method that works for that child. You have not decided upon a method yet.

For example parents can insist that the best method for their apraxic child is PROMPT and want that written as best method in the IEP. Using the words “best method” may not open the door to other strategies which best practices does and Prompt can be included in best practice. PROMPT is very good but some children are tactile defensive and it’s very difficult if you can’t get near the child’s face.

How to secure one on one private speech therapy when appropriate from the Cherab group

There are many statements we can hear as parents from school professionals such as:

“They will only offer group”

(translates they’ll only offer group and you’ll have to show why the offer is inappropriate if it is and advocate for individual or one on one therapy)

“They said they will only provide inclusive therapy”

(inclusive translates to group therapy and you’ll have to show why group inappropriate if it is and advocate for individual or one on one therapy)

Either way – as far as saying they will only offer group or inclusive therapy. Just smile and say (with your tape recorder there of course- let them know you will be bringing it as they need to know) “So you are telling me you will only offer group therapy for my son regardless of the evaluations and expert opinion on what is appropriate for him? That’s interesting. Would you mind putting that in writing for me and explain why?”

Actually, anything you hear that does not sound right -just smile and say “I’m new to this whole thing and I want to share it with some of the professionals working with my child that know more than I do as to what’s appropriate. I don’t really understand why (fill in the blank) so can you please put that in writing for me and explain why?” A school professional won’t put anything on the record that is a violation of your child’s Federal rights.

Here is a real example of a statement one parent wrote to our private support group where the school was trying replace any speech therapy with classroom placement “the team here felt that he might benefit more from our on-going language rich environment in the classroom. Sounds like your experts may feel differently.”

The classroom setting/placement is not a replacement for appropriate one on one therapy. Your child is entitled to both appropriate placement and appropriate therapy. The SLP in the school should be aware that from what I read, the experts from ASHA found that “inclusive” (group) therapy -is only appropriate for children with mild delays in speech. Debatable with moderate delays in speech, depending on the expert, and found inappropriate, possibly detrimental, for children with severe impairments in speech such as apraxia. A language enriched multisensory placement is appropriate, but your child is also entitled to working with professionals that are knowledgeable about how to provide appropriate therapy.

Two words you can’t use enough in IEP meetings and in advocating, in general, are “appropriate” and “inappropriate”

Your child is not entitled to the best -just what is appropriate. So use the word appropriate instead of “best” or “want” or “right” and use the word inappropriate instead of “worst” or “don’t want” or “wrong” If your in district school can not provide appropriate placement there are many options including something called “out of district placement” Out of district placement is where you pull the child out of the program to place them in a school (could be private) that has appropriate placement and therapy. Other options can include having an “expert” come in to train the current staff and work with your son or to keep your child in district for certain services and to pay for private therapy at home a few days a week. If you don’t ask you won’t get any of that for your child as I’ve never known for schools to just offer any of the above without advocacy. And have facts and evaluations to back up your requests. For example to advocate for sign language being included in the child’s IEP you could write “Research has shown us that when a child is exposed to gestures along with oral language their spoken speech improves. And ASHA has done numerous research projects of gesture language leading to verbal output enhancement.”

Tape Recorders and Paper Trails

For the protection of all and to prevent misunderstandings, start a paper trail and document everything. Keep a journal and jot down notes with time, dates and follow up any conversations with emails or letters.

Here is some excellent advice on letter writing from the Ohio Legal Rights Service

Communicating with Your Child’s School Through Letter Writing

Throughout your child’s school years, there will be a need to communicate with school: teachers, administrators, and others concerned with your child’s education. There are also times when the school needs to communicate with you. Some of this communication is informal, such as phone calls, comments in your child’s notebook, a discussion when picking your child up from school, or at a school function. Other forms of communication are more formal and need to be written down.

Letters provide both you and the school with a record of ideas, concerns, and suggestions. Putting your thoughts on paper gives you the opportunity to take as long as you need to:

- state your concerns,

- think over what you’ve written,

- make changes, and

- have someone else read the letter and make suggestions.

Letters also give people the opportunity to review what has been suggested or discussed. Confusion and misunderstanding can be avoided by writing down thoughts and ideas.

However, writing letters is a skill. Each letter you write will differ according to the situation, the person to whom you are writing, and the issues you are discussing. The letters contained in this section will help you in writing to the professionals involved in your child’s special education.

The term “parent” is used throughout and includes natural or adoptive parents, surrogate parents, legal guardians, or any primary caregiver who is acting in the role of a parent.

Letter Writing in General

- Put important requests in writing, even if it is not required by your school district. A letter avoids confusion and provides everyone with a record of your request.

- Always keep a copy of each letter you send. It is useful to have a folder to store copies of the letters you have written.

What do I say in my letter?

When writing any business letter, it is important to keep it short and to the point. First, start by asking yourself the following questions and include the answers in your letter:

- Why am I writing?

- What are my specific concerns?

- What are my questions?

- What would I like the person to do about this situation?

- What sort of response do I want: a letter, a meeting, a phone call, or something else?

Each letter you write should include the following basic information:

- The date on your letter.

- Your child’s full name and the name of your child’s main teacher or current class placement.

- What you want (rather than including only what you do not want). Keep it simple.

- Your address and a daytime phone number where you can be reached.

- A date for a response from and/or action by the school.

What are some other tips to keep in mind?

You want to make a good impression so that the person reading your letter will understand your request and agree with your concerns. Remember that this person may not know you, your child, or your child’s situation. Keep the tone of your letter pleasant and businesslike. Give the facts without expressing anger, frustration, blame, or other negative emotions. Some letter-writing tips include:

- Read your letter as though you are the person receiving it. Is your request clear? Have you included the important facts? Does your letter ramble? Is it likely to offend, or is the tone businesslike?

- Have someone else read your letter for you. Is your reason for writing clear? Can the reader tell what you are asking for? Would the reader say “yes” if he or she received this letter? Can your letter be improved?

- Use spell check and grammar check on the computer. Or, if you don’t have one, ask someone reliable to edit your letter before you send it.

- Always end your letter with a “thank you.”

- Keep a copy for your records.

And use tape recorders at IEP meetings. It can be viewed by some as slightly antagonistic to show up at your first IEP meeting with a tape recorder. but it’s all in how you put it. You can be very friendly and say”This is all so confusing for me and my child’s therapist and the doctor wanted to hear what is suggested as appropriate therapy and placement for (your child’s name) and I/we probably won’t remember everything that is said.” You have to let the school know that you will be taping because they will then have to tape as well.

Make sure your tape recorder either plugs in or has batteries that work, and bring extra batteries. Simple thing but I know from experience since one IEP meeting I showed up to and didn’t realize the batteries were dead until I got to the IEP meeting. I acted like my tape recorder was working and even pushed it toward people when they were talking and saying things I didn’t care for.

Tape recorders are a great way to make sure there are no misunderstandings. I appreciate there are many incredible school systems and professionals out there, probably some reading this right now. But there are situations and misunderstandings that can be stopped by a tape recorder. For example “Oh Mrs. ___ you must have misunderstood. We didn’t say he’d receive one on one therapy, we said he’d have one per one therapy, meaning one group therapy session per week.”

If your child is diagnosed with apraxia, there are strong reasons to advocate for the use of the diagnosis name apraxia on the IEP. Apraxia today is multifaceted- it’s appropriate for most to not only receive ST but OT as well.

Also see

Negotiation Skills For Parents: How To Get The Special Education Your Child With Disabilities Needs

IEP Goal Ban k

You can visit the IEP Goal Bank “This IEP Goal Bank is the place where you can “deposit” your own IEP goals/objectives and “withdraw” the goals/objectives contributed by others. Few things cause more angst in our profession than writing IEP goals/objectives! One way to simplify the process is to use the template below. If all sections of this template are filled in, then your goal/objective is measurable. ” Students receive speech and language therapy as indicated on their IEP. Services include one-to-one, in small groups, or directly in the classroom to help students overcome their involvement with a specific disorder. Some strategies include language intervention activities, articulation therapy, oral motor therapy.

One example from the IEP Goal Bank: “Long Term Goal for Articulation/ oral-motor skills: Given a structured or unstructured classroom setting, Firstname will increase speech intelligibility by use of improved oral motor characteristics and oral movements for speech sound production including (insert objectives from below) to blank % over blank consecutive trials as measured by clinician observation and data collection. PA Standard: 1.6.3/5/8/11.C ”

Oral Motor Therapy Goals

Some may be told that their district doesn’t provide oral motor therapy as it’s not an educational need. The following information will provide tools to help you advocate. Speaking of tools, Talk Tools which is founded by Sara Rosenfeld-Johnson, M.S., CCC-SLP, has programs and products for oral motor therapy. For IEPs they created a chart and a program to help therapists write IEP goals and to accurately measure progress in oral therapy activities used to improve speech clarity and feeding skill levels. These programs can help with insurance reimbursement as well.

From the Texas Speech Hearing Association here are ‘Goals of Oral-Motor/Feeding/Speech Therapy written by Renee Roy Hill, MS, CCC-SLP

Here is an example of a legal letter of appeal to a district for oral motor therapy.

Keep in mind the IEP is not limited to goals in one area. For example, occupational therapy is provided for students per IEP specification to meet the appropriate occupational therapy needs and IEP goals of students. Occupational therapists work with students independently, in groups, and/or within the classroom setting according to the needs and strengths of the student. Depending upon the individual needs of a particular child you will advocate for all therapies that are appropriate.

Sample Question and Answer About IEP

One parent from our private group asked about her first grade son. The school SLP had said she didn’t have time to evaluate her son for services.

The following answer is from our nonprofit’s SLS/MA/ EDUCATIONAL CONSULTANT, Cheryl Bennett-Johnson SLS/MA

“In order to be qualified for services, there needs to be an educational impact that greatly impacts his educational experience. The educational impact must affect his reading, writing and speaking. The therapist would have to say that his speech is not affecting his educational impact.

The fact that SLP does not have the time to evaluate new children in the first grade is not a valid reason for the child not to be evaluated.

All mom has to do is call ASHA and say the SLP doesn’t “have time to evaluate my son” to the ASHA school affairs committee and they will “go crazy” because that is not a clinical valid reason.

What is the response to intervention? If they don’t want to pick him up as IEP classification why didn’t the SLP use a consultation model with the parent and classroom teacher as to how to help the child communicate intelligibly. I can’t even believe this.

As far as what happened in kindergarten some schools do follow the guide that your school was using. If mom didn’t agree with that at that time she should have gone due process to secure speech therapy. If the child is unintelligible it can affect self-esteem and how he plays and interacts with other children. He may not even want to go to school because the other children don’t understand him and mom should have taken him for evaluations at that time.

Have mom call her department of special education and begin due process. She’ll have to have an independent evaluation first that should cover how often her child needs therapy and what type, individual or group. Who knows if it goes to due process mediation the administrative law judge may decide based on the individual service that the.child is owed additional speech services since he hasn’t been receiving either direct or consultative service since kindergarten and he is now 7 years old and unintelligible. She really has a strong case. It’s irrelevant whether he has apraxia or not as he is unintelligible.

Have they made accommodations or modifications or for his lack of verbal acuity when grading him? If he is doing well in school and he is given accommodations and modifications so he is grading well in school that may be how the school is getting around providing services. This again is why the mother needs a private evaluation.”

Reasons for one on one for apraxia can be found here

One on One Therapy A Review of Apraxia Remediation

The Cherab Foundation gratefully acknowledges permission to print the following, cited by Jennifer Hecker, a parent advocate for her apraxic son, Reed.

“The type of treatment appeared to influence whether patients improved. More patients improved and improvement was greater in Group A, individual stimulus-response treatment, than in Group B, group treatment. These results imply the way to treat AOS (Apraxia Of Speech) is to treat is aggressively by direct manipulation and not by general group discussion. This is consistent with what has been recommended (Rosenbek, 1978).

The type of treatment appeared to influence whether improvement occurred or not. Four of the five patients who did not improve received group treatment with no direct manipulation of their motor speech deficit.” Apraxia of Speech: Physiology, Acoustics, Linguistics, Management. Rosenbek et al. 1984

“The frequency of professional speech assistance is critical in the habilitation of children with developmental apraxia of speech. This disability calls for all-out attention and deserve serious instruction to the limits of the child’s attention and motivation. When normal children begin their formal education, they do not go to school two or three times a week for just a half-hour at a time, even in kindergarten. Thus, I do no expect to provide special education for children with developmental apraxia of speech on a cursory basis, for it may be the most important part of the entire education.” Current Therapy of Communication Disorders, Dysarthria and Apraxia. William H. Perkins 1984

“They use the term developmental apraxia to describe a disorder that is not confined to the phonologic and motoric aspects of speech production but includes difficulty in selection and sequencing of syntactic and lexical units during utterance productions. Most clinicians agree that planning the appropriate treatment approach and methods is crucial to the efficacy of intervention. A variety of factors can facilitate treatment of DAS. DAS is often characterized as being resistant to traditional methods of treatment. Group therapy decreases the potential of responses per session for each child and therefore, the motor practice needed by children with apraxia and dysarthria.” Treatment of Motor Speech Disorders in Children by Edythe Strand in “Seminars of Speech and Language” Vol.16, No. 2. May 1995

“Early stages of treatment need to be carried out on a one-to-one basis for it is only in this way that the patient can learn to develop his own particular strengths and adopt compensatory measures for weaknesses.” Disorders of Articulation, Aspects of Dysarthria and Verbal Apraxia. Margaret Edwards 1984″These children do not seem to make good progress with the usual approaches to clinical treatment of articulation problems. Carefully structures programs that combine muscle movement, speech sound production, and sometimes even work on grammar seem to get better results.” “Developmental Verbal Dyspraxia” on Healthtouch Online, ASHA website

“Children must be seen one-on-one, at least in the early stages of treatment.” Nancy Kaufman, author of the Kaufman Speech Praxis Test and expert on Apraxia, on The Kaufman Children’s Center for Speech and Language Disorders website.

“However, many of the theories, principles, and hierarchies described for adult apraxics are potentially helpful to the clinician designing motor-programming remedial program for an individual child. (We stress the word individual since the program development for children with DAS must meet the individual, and often unique, needs of each child.)” Intensive services are needed for the child with DAS. Children with DAS are reported to make slow progress in the remediation of their speech problems. They seem to require a great deal of professional service, typically done on an individual basis. Therefore, clinicians working with DAS must accommodate this need and schedule as much intervention time with the child as the child and/or his/her schedule can allow. The definition “intensive” varies from clinician to clinician and from work setting to work setting. Rosenbek (1985), when discussing therapy with adult apraxics, defines the word as meaning that the patient and the clinician should have daily sessions: Macaluso Haynes (1978), Haynes (1985), and Blakeley (1983) also advocate daily remediation sessions.” Also, “our experience has been that the overall outcome has been best for those children with DAS who were identified as possibly exhibiting DAS and received services as very young children.” Developmental Apraxia of Speech, Theory and Clinical Practice. Penelope Hall et al. 1994

“We recommend therapy as intensively and as often as possible. Five short sessions (e.g., 30 minutes) a week is better than two 90 minute sessions. Regression will occur if the therapy is discontinued for a long time (e.g. over the summer). Most of the therapy (2-3/week) must be provided individually. If group therapy is provided, it will not help unless the other children in the group have the same diagnoses and are at the same level phonologically.”Shelley Velleman, authority and published author on Apraxia, on her website (velleman.html). “Our clinic has had tremendous success with the half-hour format, we find these sessions to be very intense, packed with therapy, and have little down time. The earlier and more intensive the intervention, the more successful the therapy. Group therapy can be effective for articulation disorders and some phonological processing disorder, but children with Apraxia really need intensive individual therapy.” Nancy Lucker-Lazerson, MA, CCC-SLP, and Clinic Coordinator for the Scottish Rite Clinic for Childhood Language Disorders San Diego.

“A few major principles, in particular, have direct relevance to the treatment of motor speech disorders. The most obvious, yet surprisingly often disregarded, is that of repetitive practice. The pairing of auditory and visual stimuli is included in most approaches, and intensive, frequent, and systematic practice toward habituation of a particular movement pattern is suggested instead of teaching isolated phonemes. It is important to consider the treatment needs of each child and attempt to find creative solutions that allow frequent individual treatment for children that will most benefit.” Childhood Motor Speech Disorders Edythe Strand

“Given the controlled conditions stipulated in the studies…, it is clear that speech dyspraxia can respond to therapy. All approaches involved an intensive pattern of therapy. Even if not seen daily by a therapist, patients carried out daily practice.” Acquired Speech Dyspraxia, Disorders of Communication: The Science of Intervention. Margaret M. Leahy 1989

“Consistent and frequent therapy sessions are recommended. The intensity and duration of each session will depend on the child. At least three sessions per week are recommended for the child to make consistent progress.” Easy Does it for Apraxia-Preschool, Materials Book. Robin Strode and Catherine Chamberlain

“In stark contrast, the children with apraxia of speech whose parent stated that three-quarters of their child’s speech could be understood following treatment required 151 individual sessions (ranging from 144-168). In other words, the children with apraxia of speech required 81% more individual treatment sessions than the children with severe phonological disorders in order to achieve a similar function outcome.” Functional treatment outcomes for young children with motor-speech disorders by Thomas Campbell in Clinical Management of Motor Speech Disorders A.J. Caruso and E.A. Strand 1999.

1:1 Therapy Question Sent To Children’s Apraxia Network:

Advice From our nonprofit’s SLS/MA/ EDUCATIONAL CONSULTANT, Cheryl Bennett-Johnson SLS/MAhttp://www.cherabfoundation.org/about/advisoryboard/cheryl-bennett-johnson-m-a-slseducational-consultant/

It is interesting to note that when a child is receiving Early Intervention services in the home, therapy is 1:1. It is also interesting to note that children as young as 6 months of age have received 1:1 services. Every apraxic child is different, with a diagnosis of severe apraxia, the child would benefit from 1:1 therapy. What data is the school SLP (Speech Language Pathologist) presenting indicating that the age of 5 is too young for 1:1 services?

Remember when a request for services is not given as requested, the denying party must give a written rationale as to why. The IEP (Individualized Education Program) is an individualized Education Program. How will the SLP (Speech & Language Pathologist) address the severe oral motor needs of the child within the group setting? What are the short and long-term goals and objectives that are specific to the nature of this child’s severe apraxia? Does the SLP plan to devote x amount of minutes providing 1:1 therapy to your child within the group setting? Your child’s disability of apraxia affects his involvement and progress in the general curriculum and access to nonacademic and extracurricular activities due to the fact that he is not able to communicate appropriately to school personnel when needed and communicate effectively through speech and/or writing to class- mates and teachers. The severity of his disability warrants 1:1 speech therapy intervention. Your child’s disability of apraxia of speech affects his ability to engage in age relevant behaviors that typical students of the same age would be expected to be performing or would have achieved {IDEA-Code of Federal Regulations (C.F.R.): 34 C.F R.300.347 (a)(1)(i) Statue 20 United State Code (U.S.C.) 1414 (d)(1)(A)(i)(1).

I am requesting that the parent draft a letter to the Dr. of the Child Study Team including the information listed above. Indicate that you are not in agreement with the type /amount/duration of the speech therapy services that will be provided to your child. State that you are seeking 1:1 therapy services for your child because. Send the letter certified receipt return requested. Send a copy to the SLP, the District Superintendent of Schools, and Board of Education President. Severe Apraxia requires the parent to advocate for 1:1 services in the area of speech therapy.

Penelope Hall, Linda Jordan and Donald Robin, Developmental Apraxia of Speech: Theory and Clinical Practice:

“Intensive services are needed for the child with DAS. Children with DAS are reported to make slow progress in the remediation of their speech problem. They seem to require a great deal of professional service, typically done on an individual basis. Therefore, clinicians working with DAS must accommodate this need and schedule as much intervention time with the child as the child and/or his/her circumstances can allow Thus, the clinician may be thrust into the position of becoming an advocate on behalf of the child to assure that services are provided as frequently as possible. In some cases, the clinician may need to help the family find the financial resources or assistance they may need to cover the costs of professional service; a child with DAS can quickly become an expensive child to his/her family or school system base of the amount of therapy they typically require.

“The roles of parents, teachers, peers, and siblings in a child’s program of remediation will also vary with the circumstances. If the child with DAS can tolerate additional work and interacts well with the selected individual, the speech-language pathologist may include family and/or teachers in the overall programming to provide additional response opportunities for the child to reinforce and strengthen performance on a particular speech target. Creaghead, Newman, and Secord (1989) stated that “nightly parental drill… is a necessity” (p.274). However, in today’s society, we recognize that the involvement of the family and teachers in the extra remedial programming may not be a practical recommendation to pursue.

“The definition of ‘intensive’ varies from clinician to clinician and from work setting to work setting. Rosenbek (1985), when discussing therapy with adult apraxics, defines the word as meaning that the patient and the clinician should have daily sessions; Macaluso-Haynes (1978), Haynes (1985), and Blakeley (1983) also advocate daily remediation sessions. Blakeley (1983, p.27) stated that ‘I do not expect to provide speech education for children with developmental apraxia of speech on a cursory basis for it may be the most important part of their entire education.’ …”Edythe Strand,

“A few major principles, in particular, have direct relevance to the treatment of motor speech disorder. The most obvious, yet surprisingly often disregarded, is that of repetitive practice. Motor learning occurs and becomes habituated toward more automatic processing only if enough practice trials occur.” (p, 130)

“Pairing of auditory and visual stimuli is included in most approaches, and intensive, frequent, and systematic practice toward habituation of a particular movement pattern is suggested instead of teaching isolated phonemes.” (p 130)

“DAS is often characterized as being resistant to traditional methods of treatment. It may be that traditional methods are not to blame so much as: (1) The child’s individual needs have not been given enough attention, (2) principles of motor learning (e.g. sufficient practice, knowledge of results) have not been sufficiently implemented into treatment, (3) not enough attention has been paid to varying the oral relationship between stimulus and the response, and (4) sessions are too infrequent to allow sufficient motor practice…”(p 131)

“The principles of treatment for motor speech disorders just discussed may be hard to implement in some clinical settings, especially the public schools. Large caseload demands often prohibit individual treatment. Group therapy decreases the potential number of responses per session for each child and, therefore, the motor practice needed by children with apraxia or dysarthria. The schedules of itinerant therapists often prevent them from seeing a child more than once or twice a week, which would greatly impede potential progress. Although it may not always be possible to have an optimum clinical situation, it is important to consider the treatment needs of each child and attempt to find creative solutions that allow frequent individual treatment for those children who will most benefit.” (p 137) Mary Pannbacker, “Management Strategies for Developmental Apraxia of Speech: A Review of Literature,” Journal of Communication Disorders, 21 (1988):

“Rosenbek and associates outlined the following principles for management of developmental apraxia of speech: acquisition of near normal volitional speech as physiological limitations will allow; emphasizing movement sequences; generating task continue according to phonetic principles; limiting number of stimuli; intensive systematic drill; use of visual modality; and facilitating response adequacy with systematic use of rhythm, intonation, stress, and motor movements.”

Macaluso-Haynes reviewed management procedures and “these techniques involved: concentrated drill on performance; imitation of sustained vowels and consonants followed by production of simple syllable shapes; movement patterns and sequences of sounds; avoidance of auditory discrimination drills; slow rate; self-monitoring; core vocabulary; carrier phrases; rhythm; intensive, frequent, and systematic drill, and orosensory perceptual awareness” Niklas Miller, “Acquired Speech Dyspraxia,” Disorders of Communication: The Science of Intervention, Margaret M. Leahy, c. 1989, Chapter 12:

“The work of LaPointe and Dworkin demonstrated improvement and the patients in the report by Wertz improved if they received motor speech training, but not as a result of general language therapy. Given the controlled conditions stipulated in the studies…, it is clear that speech dyspraxia can respond to therapy. All approaches involved an intensive pattern of therapy. Even if not seen daily be a therapist, patients carried out daily practice. The studies also re-emphasize the need for objective, principled structuring of therapy steps and the assessments that monitor them — establishing baselines and controls, systematically manipulating variables (input, response demands, etc.) and monitoring which mode and combination of therapies are providing most effective for the individual…”

Robin Strode and Catherine Chamberlain, Easy Does It for Apraxia– Preschool, Materials Book:

“Daily practice is critical for consistent progress. Children with DVA [developmental verbal apraxia] have difficulty locking in the motor sequencing for speech. Frequent short practice sessions are very important.”

“Consistent and frequent therapy sessions are recommended. The intensity and duration of each session will depend on the child. At least three sessions per week are recommended for the child to make consistent progress.”

The IEP is at the heart of legislation which mandates a free, appropriate education for children with disabilities in public schools.

The IEP was an integral part of the original federal legislation enacted in 1975, Public Law 94-142, The Education of All Handicapped Children Act (EHA).

In 1990, this law was reauthorized by Congress and was renamed Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), Public Law 101-476. The IEP continues to be the cornerstone of a quality educational experience for a child who receives special education services.

The IEP is a document that directs the entire school program of the child. It is an agreement between the school and the parents on how the child will be educated, and it is written, jointly, by the parents and school personnel.

There are three main parts in developing an IEP:

1. Formal and informal assessment and evaluation of the child by parents, educators, and qualified professionals to determine the child’s current level of functioning, strengths, and needs.

2. Meetings (called “staffmgs”) where school personnel and parents make decisions together about the education plan and placement for the child. This team then writes the IEP document together.

3. The process of putting the IEP into practice in the child’s everyday life at school. The IEP is a written commitment of services, which the school is responsible for providing. While the school cannot be held responsible if a child does not meet his/her goals. the school must make good faith efforts at helping the child achieve the goals.

The IEP is to be developed or revised by the following:

1. The parents (all staffings).

2. The child, if appropriate (all staffings).

3. The special education administrator or designee (initial. triennial. and review staffmgs).

4. The building administrator or designee (initial and triennial staffings).

5. The child’s special and regular educators (all staffings).

6. Other individuals who know the child well. at the request of the parents or the school (all staffings).

The IEP must Include the following information:

1. The child’s current level of functioning, strengths, and needs in these areas:

A. Physical abilities

B. Communication abilities

C. Thinking abilities

D. Social and emotional behavior

E. Developmental or educational growth

2. Annual goals with measurable short-term objectives.

3. Specific related services and characteristics of service (modifications) that the school will provide.

4. A statement of the child’s placement including time spent in the regular classroom and the supports to be provided by the school.

5. The date the child begins receiving special education services and the expected length of services.

UNDER THE LAW

An IEP must be written for each child with a disability who qualifies for special education services.

A review staffing must be held before a change in the child’s placement is considered.

An IEP must be reviewed at least once each year but may be reviewed more often if necessary.

A new IEP must be written every three years with new assessments and evaluations (a triennial staffing).

All children with disabilities are guaranteed:

A free, appropriate education to meet their individual needs.

A fair assessment of their strengths and abilities as well as their

needs and disabilities.

An appropriate placement with children who do not have disabilities, to the maximum extent possible (least restrictive environment).

Appropriate supplementary aids and services regardless of their placement.

Things to remember:

1. A child’s program and placement are determined only after the IEP is developed based on the child’s unique needs. The IEP is not based on what is available from the school district: It can only be based on the needs of the child. A change of services or placement can be made only by the staffmg team, which includes the parents. It cannot be done by school administration.

2. The IEP meeting must be at a time and place agreed upon by the parents and the school personnel.

3. Parents are equal participants in developing, reviewing, and revising their child’s IEP. It is important for parents to take the time and make the effort to become informed, effective members of the staffing team.

4. Parents have the right and the responsibility to read and understand the IEP before they sign it and to ask questions if they don’t understand. The IEP does not have to be signed by the parents at the staffing; they may take it home and study It before signing.

5. Parents should make sure they have a copy of the entire IEP for their records.

6. Parents can set progress review dates with their child’s teacher(s) and follow through, keeping the lines of communication open.

7. Parents may ask for an evaluation whenever they feel is necessary.

8. Parents may request a staffing at any time If they believe the IEP needs to be changed In order to best meet the child’s needs.

The entire purpose of the IEP is to benefit the child. Remember that every child is a whole person who needs to learn. to laugh. to play. and to make friends. Social success is as important as educational success. All children need to feel they “belong.” Studies indicate that children with disabilities who feel they belong and are an Important part of their class, their school, or their group learn better than those who feel left out.

A child with a disability is a child first and foremost. He/she should be provided \with the same opportunities for healthy childhood development that other children have. It is important that a child with a disability be included in the everyday activities at school. The IEP can and should address this critical need of the child.

The Individualized Education Plan is a tool to help each child open the door to achieving his/her place in the world. And PARENTS hold the key!

ePEAKnt Center. Inc.. 6055 Lehman Drtve. #101. Colorado Spllngs. CO 80918 (719)531-9400. (719)531-9403 rmD). 1-800-284-0251 for parents In Colorado. FAX(719)531-9452 More info here

Your Child’s IEP: Practical and Legal Guidance for Parents

By: Peter W. D. Wright and Pamela Darr Wright (2003)

Editor’s note: This article was published before the 2004 reauthorization of IDEA. While much of the law remains the same, some changes have been made to the language and procedures. We continue to offer this article because it provides valuable information that is still relevant to the current law. For more information on the recent changes, visit our 2004 IDEA Update page.

Introduction

If you are like many parents, when you receive a telephone call or letter inviting you to an IEP meeting, you respond with anxiety. Few parents look forward to attending IEP meetings. You may feel anxious, confused and inadequate at school meetings. What is your role? What do you have to offer? What should you do? Say? Not do?

Because they are not educators, most parents don’t understand that they have a unique role to play in the IEP process.

Parents are the experts on their child.

Think about it. You spend hours every week in the company of your child. You make casual observations about your child in hundreds of different situations. You are emotionally connected to and attuned to your child. You notice small but important changes in your child’s behavior and emotions that may be overlooked by others. You have very specialized knowledge about your child. This also helps to explain why your perspective about your child may be quite different from that of the educators who only observe your child in the school setting.

Why do parents feel so anxious, inadequate and intimidated in school meetings? Most parents seem to believe that because they are not “trained educators” – and don’t speak “education jargon” – they have little of value to contribute to discussions about their child’s education.

The “parental role”

Perhaps we can explain “parental role” more clearly if we change the facts to illustrate our point.

Think back to the last time your child was sick and you saw a doctor for medical treatment. You provided the doctor or nurse with information about the child’s symptoms and general health. They asked you for your observations – because you are more familiar with your child.

Good health care providers elicit this kind of information from parents. They do not assume that unless parents have medical training, they have little of value to offer! When health care professionals diagnose and treat children, they gather information from different sources. Observations of the child are an important source of information. The doctor’s own medical observations and lab tests are added to the information you provide from your own personal observations.

Do you need to be medically trained before you have any valid or important information to offer the doctor about your child’s health? Of course not.

Decision-making: medical v. educational

To diagnose a child’s problem and develop a good treatment plan, doctors need more than subjective observations. Regardless of their skill and experience, in most cases, doctors need objective information about the child. Information from diagnostic tests provides them with objective information. When medical specialists confront a problem, they gather information – information from observations by themselves and others and from objective testing.

Special education decision-making is similar to medical decision-making. The principles are the same. Sound educational decision-making includes observations by people who know the child well and objective information from various tests and assessments.

In both medical and educational situations, a child is having problems that must be correctly identified. The Individualized Education Plan (IEP) is similar to a medical treatment plan. The IEP includes information about the child’s present levels of performance on various tests and measures. The IEP also includes information about goals and objectives for the child, specifically how educational problems will be addressed. The IEP should also include ways for parents and educators to measure the child’s progress toward the goals and objectives.

How to evaluate progress

Now, think back to that last time your child was sick and needed medical attention. You left the doctor’s office with some sort of plan – and an appointment to return for a follow-up visit. When you returned for the follow-up visit, you were asked more questions about how your child was doing – again, you were asked about your observations. This information helped the doctor decide whether or not your child was responding appropriately to treatment. If you advised that your child was not responding to the treatment and continued to have problems, then the doctor knew that more diagnostic work was needed and that the treatment plan may need to be changed.

Special education situations are similar to medical situations – except that these decisions are made by a group of people called the IEP Team or IEP Committee. As the parent, you are a member of the IEP team. Before the IEP Team can develop an appropriate plan (IEP) for your child, the child’s problems must be accurately identified and described.

To make an accurate diagnosis, the IEP team will need to gather information from many sources. This information will include subjective observations of the child in various environments – including the home environment and the classroom. The information should also include objective testing. Objective testing needs to be done to measure the extent of the child’s problems and provide benchmarks to measure progress or lack of progress over time.

If your child receives special education services, you know that a new educational plan or IEP must be developed for your child at least once a year. Why is this?

Children grow and change rapidly. Their educational needs also change rapidly. In many cases, the IEP needs to be revised more often than once a year. Parents and educators can ask for a meeting to revise the IEP more often than once a year – and new IEPs can be developed as often as necessary.

The child’s educational plan, i.e. the IEP, should always include information from objective testing and information provided by people – including the parents and teachers – who observe the child frequently.

What should be in my child’s IEP?

The IEP should accurately describe your child’s learning problems and how these problems are going to be dealt with.

One of the best and clearest ways to describe your child’s unique problems is to include information from the evaluations. The IEP document should contain a statement of the child’s present levels of educational performance. If your child has reading problems, the IEP should include reading subtest scores. If your child has problems in math calculation, the IEP should include the math calculation subtest scores. To help you understand what these scores mean, you should read our article “Understanding Tests and Measurements.”

Goals and objectives

The IEP should also include a statement of measurable annual goals, including benchmarks and short- term objectives. The goals and objectives should be related to your child’s needs that result from the disability and should enable your child to be involved in and progress in the general curriculum. The goals and objectives should meet other educational needs that result from your child’s disability.

The IEP goals should focus on reducing or eliminating the child’s problems. The short term objectives should provide you and the teacher with ways to measure educational progress. Are reading decoding skills being mastered? How do you know this? An IEP should include ways for you and the teacher to objectively measure your child’s progress or lack of progress (regression) in the special education program.

In our work, we see many IEPs that are not appropriate. These IEPs do not include goals and objectives that are relevant to the child’s educational problems. In one of our cases, the IEP for a dyslexic child with severe problems in reading and writing included goals to improve his “higher level thinking skills,” his “map reading skills” and his “assertiveness” – but no goals to improve his reading and written language skills. This is a common problem – IEP goals that sound good but don’t address the child’s real problems in reading, writing or arithmetic.

If you take your child to the doctor for a bad cough, you want a cough treated. You won’t have much confidence in a doctor who ignores a cough – and gives you a prescription for ulcer medicine!

Measuring progress: Subjective observations or objective testing?

Let’s return to our medical example. Your son John complained that his throat was sore. You see that his throat is red. His skin is hot to the touch. He is sleepy and lethargic. These are your observations.

Based on concerns raised by your subjective observations, you take John to the doctor. After the examination, the doctor will add subjective observations to yours. Objective testing will be done. When John’s temperature is measured, it is 104. Preliminary lab work shows that John has an elevated white count. A strep test is positive. These objective tests suggest that John has an infection.

Based on information from subjective observations and objective tests, the doctor develops a treatment plan – including a course of antibiotics. Later, you and John return – and you share your ongoing observations with the doctor. John’s temperature returned to normal a few days ago. His throat appears normal. These are your subjective observations.

Subjective observations provide valuable information – but in many cases, they will not provide sufficient evidence that John’s infection is gone. After John’s doctor makes additional observations – she may order additional objective testing. Why?

You cannot see disease-causing bacteria. To test for the presence of bacteria, you must do objective testing. Unless you get objective testing, you cannot know if John’s infection has dissipated.

By the same token, you will not always know that your child is acquiring skills in reading, writing or arithmetic – unless you get objective testing of these skills.

How will you know if the IEP plan is working? Should you rely on your subjective observations? The teacher’s subjective observations? Or should you get additional information from objective testing?

Is your child “really making progress?”

We have worked with hundreds of families who were assured that their child was “really making progress.” Although the parents did not see evidence of this “progress,” they placed their trust in the teachers. After their child was evaluated, these parents were horrified to learn that their suspicions were correct – and the professional educators were wrong.

In one of our cases, Jay, an eight year old boy with average intelligence, received special education services for two years – through all of kindergarten and first grade. Jay’s parents felt that he was not learning how to read and write like other children his age. The regular education and special education teachers repeatedly assured the parents that Jay was “really making progress.” The principal also told the parents that Jay was “really making progress.”

After he completed first grade, the parents had Jay tested by a private sector diagnostician. The results of the private testing? Jay’s abilities were in the average to above average range. His skills in Reading and Written Language were at the early to mid-Kindergarten level. After two years of special education, Jay had not learned to read or write.

When teachers tell you that your child is “making progress,” that teacher is giving you an opinion based on subjective observations. As you just saw in Jay’s case, opinions and subjective observations may not give you accurate information.

If you have questions or concerns about whether your child is really making progress, you need to get objective testing of the academic skills areas – reading, writing, arithmetic and spelling. After you get the results of objective testing, you will know whether or not your child is really making progress toward the goals in the IEP.

The IEP: The “Centerpiece” of Special Education Law

The IEP has been called the “centerpiece” of the special education law. As you read through this article, you will learn more about the law – and the rights that ensure that all children who need special education receive appropriate services. You will read about cases that have been decided around the country. Each of these cases is having an impact on the special education system today – improving the quality of special education services for all handicapped children – including your child.

After you learn about the law, regulations, and cases, you will know how to write an IEP. If the IEP is written properly, you will be able to measure your child’s progress.

We said this earlier – and it bears repeating. If you measure your child’s progress – using objective measures – you will know whether your child is actually learning and benefiting from the program. If objective testing shows that your child is not learning and progressing as expected, then you know that the educational plan is not appropriate and your child is regressing.

If your child is not learning and making progress – with progress measured objectively – the IEP should be revised. (For more information about revising the IEP if child does not make progress, see Appendix A of the Regulations).

Read our companion article: Understanding Tests and Measurements for the Parent and Advocate. When you master the information in these articles, you’ll be on your way to developing good IEPs for your child.

Law & regulations

The IDEA statute was amended in June, 1997. When the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) was amended, changes were made in the section about “Individualized Educational Programs.” The new federal regulations were issued in March, 1999. You will find helpful information about IEPs in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) and Appendix A of the Regulations.

(NOTE: The IDEA statute, regulations and Appendix A are in Wrightslaw: Special Education Law. The Regulations and Appendix A are also on the Wrightslaw site. The Regulations page is here

What is the parent’s role in the IEP process?

“The parents of a child with a disability are expected to be equal participants along with school personnel, in developing, reviewing, and revising the IEP of their child.” This role is an active role in which the parents

(1) provide critical information regarding the strengths of their child and express their concerns for enhancing the education of their child;

(2) participate in discussions about the child’s needs for special education and related services and supplementary aids and services; and

(3) join with the other participants in deciding how the child will be involved and progress in the general curriculum and participate in State and district-wide assessments, and what services the agency will provide to the child and in what setting.

What Happens to a Child’s Special Education Program When the Family Moves

Advice from LD Online

Question

We are moving to another state this summer. Our son, William, has a learning disability and is in special education. How can I make sure that he continues to receive the special education services that he needs?

Answer

“We strongly suggest that prior to the move, you contact the special education department of the district or state agency where you plan to live to find out their eligibility criteria for learning disabilities. You might also contact the LDA state or local affiliate in the state to which you are moving. The names and addresses of state and local affiliate presidents are on file in the LDA National Office. Talking with another parent may be reassuring.

When you get to the new school district, enroll your child immediately. Sign a release at the new school to enable the district to obtain copies of your son’s cumulative and special education records from his previous school. You may save valuable time if you bring copies of your son’s latest evaluation and his current IEP with you.

The US Department of Education, in a letter dated December 5,1995, addressed the responsibilities of states and school districts to students with disabilities when they transfer from one state to another. Under Part B of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), the school district to which you are moving is not required to accept your child’s most recent evaluation or to implement your child’s Individualized Education Program (IEP). The Education Department letter does, however, spell out guidelines for the receiving state and district.

When a family moves from one state to another, the receiving school district must first determine whether it will adopt the child’s most recent evaluation and IEP. If the receiving district determines that the previous evaluation complies with their state laws as well as Part B of IDEA, they may adopt the evaluation and provide the parent notice in accordance with 34 CFR § 300.504 (a).

The receiving district must also examine the student’s IEP using the same criteria compliance with state law and Part B of IDEA. If the receiving district determines the IEP is appropriate and can be implemented, no IEP meeting needs to be held if the parent is satisfied with the current IEP. If either the parent or the school district is dissatisfied with the existing IEP, an IEP meeting must be conducted no later than 30 calendar days after the receiving school district accepts the eligibility determination and evaluation from the previous school district.

If the receiving school district does not accept previous evaluation, anew one must be done <cite>without due delay</cite> after provision of proper parental notice under 34 CFR § 300.128, § 300.220, and § 300.504 (a). The new evaluation must be treated as a <cite>preplacement evaluation</cite> under 34 CFR §300.531, and prior parental consent must be obtained (34 CFR § 300.504 (b)( l )(i)). While being evaluated, the student may receive special education services if an interim IEP is agreed to by the district and parent. If there is a disagreement, the student will be placed in regular education. Once the receiving district completes its assessment, an IEP meeting must be held no more than 30 calendar days after the date of eligibility determination (34 CFR § 300.343(c)). At that meeting an appropriate IEP should be developed and adopted.

Parents may initiate an impartial due process hearing under 34 CFR § 300.506 if they disagree with either the new evaluation or the proposed IEP. Pending the hearing, the student could be placed in the program proposed by the receiving district, if the parent agrees or in another placement on which agreement can be reached. If agreement on an interim placement is not reached, the district is not required to implement the previous IEP or to approximate services provided under the previous IEP. In such a situation, the student would be placed in a regular education program.

Remember, even if your son is not eligible for special education services under IDEA in the new school district, he may be eligible under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Information on Section 504 can be obtained from your state education agency or from LDA.”

Legal decisions

To help educate you about IEPs and what they should include…read more

Appendix A

Appendix A is an important tool to use when developing a child’s IEP. You can download Appendix A from the Wrightslaw site

You can also get Appendix A and other resources at The National Information Center for Children and Youth with Disabilities (NICHCY):

Get a complete list of the special education publications from NICHCY.

Pete and Pam Wright c/o The Special Ed Advocate P.O. Box 1008 Deltaville, VA 23043 Phone: 804-257-0857 website: email: webmaster@wrightslaw.com

IEP Goals, Objectives, and Sample Letters to Teachers

Summer IEP Extended School Year

Guideline for Speech-Language Eligibility Criteria/Severity Intervention Matrix for Schools

Insurance Coverage Tips For Speech And Other Special Needs Therapies