Testing your child’s ability on their disability is a violation of your child’s civil rights in the United States. You’d think it wouldn’t happen then, but you’d think wrong if you are talking about communication impairments. When speaking in regards to civil rights I like to refer to communication impairments as a verbal disability. A disability can be temporary or permanent.

Testing your child’s ability on their disability is a violation of your child’s civil rights in the United States. You’d think it wouldn’t happen then, but you’d think wrong if you are talking about communication impairments. When speaking in regards to civil rights I like to refer to communication impairments as a verbal disability. A disability can be temporary or permanent.

Outside of a hearing impairment, where there are laws in place, for most others with a temporary or permanent verbal disability there is a good chance a verbal based test was used to judge your child’s receptive and cognitive ability.

While there are numerous nonverbal tests that can be used such as the Universal Nonverbal Intelligence Test (UNIT) or Raven’s Progressive Matrices or RPM, there are tests used such as the WISC which are language based and thus in most cases inappropriate to give to someone with a verbal disability unless the professionals pulls from it to use subtests they find appropriate. And if this test is used it should clearly not be used to make predictions on your child’s future academic ability or to diagnose a language impairment.

When it comes to testing both the test used as well as the professional providing the test is key. Children with communication impairments provide nonverbal cues so you want someone who is knowledgeable about working with a child with a verbal disability.

Preschool testing can be provided private by an SLP, developmental pediatrician or neurologist, and if school age a psychologist. If your child has an IEP or is being assessed for an IEP, private testing outside of the school is highly recommended. And in that regard, second opinions are also highly recommended.

Dr. Paula Tallal who is an expert in this area, and a consultant to the Cherab Foundation, once told me that it’s extremely difficult to get an accurate cognitive assessment for anyone with a communication impairment, even an adult. So if your child scores low on certain tests as mine did, don’t believe that is the proof for your child’s future as mine proved that testing wrong.

“Most doctors do not conduct as extensive a battery of speech and language tests that a speech pathologist does. Instead, they use pictures, toys, crayons and paper to assess the child’s pretend play and hand grasp. Sometimes, they utilize developmental scales to judge the level at which your child is functioning compared to other children his age. Some examples of these are the Gesell Developmental Schedules-Revised, the Early Language Milestones Scale-2 (ELMS), the Cognitive Adaptive Test/Clinical Linguistic and Auditory Milestone Scale CAT/CLAMS, and the Lexington Developmental Scale.” ~The Late Talker book

“Formal cognitive testing is typically performed by a licensed psychologist or neuropsychologist. Make sure that you are referred to one who is familiar with testing nonverbal or unintelligible children and that they use age-appropriate nonverbal intelligence tests, such as the Leiter, for children two years old and up, the Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children (KABC) for children four years old and older, or the Comprehensive Test of Nonverbal Intelligence, (CTONI) for those aged six and above.” ~The Late Talker book

“Some of the more popular language tests or scales that your SLP may use include:

The Rosseti Infant Toddler Language Scale (Birth to three years)

The Preschool Language Scale (PLS-3) (Birth to six years)

The Clinical Evaluation of Language Functions (CELF)-Preschool (three through six years) and the CELF-3 (six through twenty-one years)

The Receptive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test (ROWVT) (two through eighteen years)

The Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test-Revised (EOWPVT) (two through twelve years)

The Test of Early Language Development-3(TELD-3) (two through seven years)” ~The Late Talker book

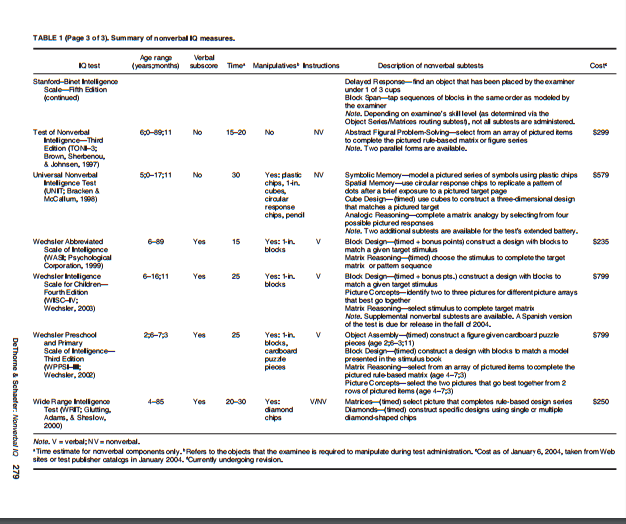

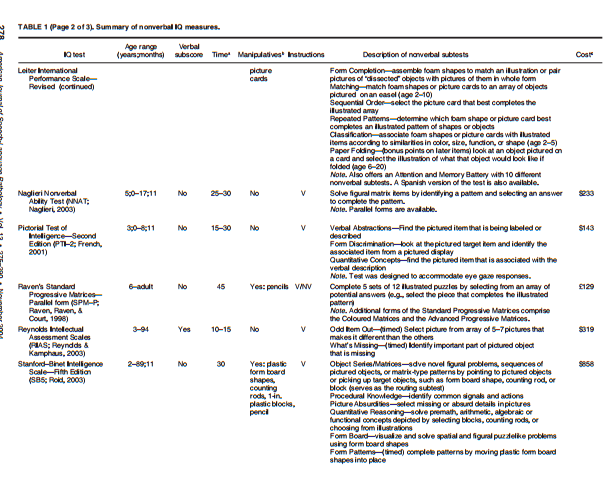

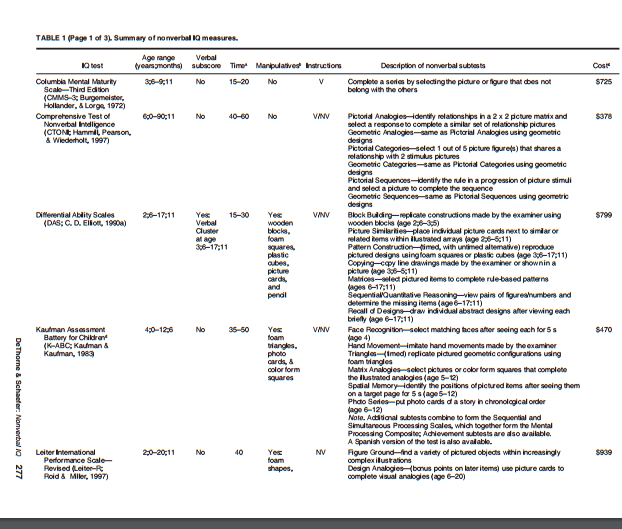

Charts from A Guide to Child Nonverbal IQ Measures Pennsylvania State University

“In sum, the present article presented information regarding 16 commonly used child nonverbal IQ measures, highlighted important distinctions among them, and provided recommendations for test selection and interpretation. When selecting a nonverbal IQ measure for children with language difficulties, we currently recommend the UNIT (Bracken & McCallum, 1998) for cases of highstakes assessment and the TONI–3 (Brown et al., 1997) for cases of low-stakes assessment. Regardless of which specific test is administered, professionals are encouraged to be cognizant of each test’s strengths and limitations, including its psychometric properties and its potential”

Having the appropriate test is key, but so is finding the right professional who is knowledgeable about working with a communication impaired child. I have found those that are used to working with the hearing impaired population to be wonderful because most don’t have a negative stereotype against a verbal disability, meaning they don’t equate ability to speak with ability to think and learn, and they have access to appropriate testing. Below is a fabulous explanation of how to test a child with a verbal disability by a school neuropsychologist.

Summary of assessment procedures Children with significant language and motor skills delays

by Robert E. Friedle, Ph.D. Clinical/Neuropsychologist

Formalized assessment of children with low incidence disabilities does not often provide accurate or practical information about their cognitive functioning skills. Such assessment does provide evidence that these children often have not learned how to respond in direct one-to-one reciprocal testing situations, or that they are unable to respond in those situations due to the nature of their disabilities. The lack of response should not be considered then, necessarily, as a global and fixed delay in cognitive/intellectual potential. Developmental theorists and practitioners have long known that cognitive growth is not only enhanced, but also dependent upon opportunities to experience a wide variety of sensory stimuli in an interactive relationship. Problem solving skills, analytical reasoning, and decision-making are all formalized, cognitively, when integration of information is ongoing. Language and motor skill limitations often prevent the integration and experiences and thus certain cognitive growth waits until such experiences may be provided.

Children may have learned to problem-solve and reason in ways that are not assessed by formalized evaluations and are only recognizable when the child is allowed to experience sensory information in a manner most productive to them. It is often then necessary for the examiner to assess what opportunities and experiences the child may have had already, how an assessment may prompt the child to show what they can do with various stimuli and how problem solving, analytical, and decision making skills can be exhibited by a child in a non-formalized approach.

The purpose of an assessment request has to be relevant to the child and to their experiences, i.e. the child needs to see some purpose for providing a response. A very simple example of this premise is: asking them to name an object may result in no response, but asking them to get the object may show a knowledgeable response.

Children with language and motor deficits often play within the restrictions that their limitations have presented and this “changed” pattern of play, from what is seen with non-disabled children, can be a direct reflection of their ability to problem solve and reason in play. An example for this may be when a child finds that laying things down and flat makes it easier to manipulate, or that moving things closer or out of the way facilitates motor planning and play. Often the child may see no purpose to expand experiences, or have not figured out independently how to change their play patterns.

Restrictions in movement or language limit the experiences a child has had with objects and stimuli. The need to practice simple movements, to hear the words that go along with those movements, and then to ask a child to duplicate the movements and/or the words can greatly facilitate cognitive growth. If a child can readily make such duplicated responses then the potential for cognitive growth at that point presents no limitations. An examiner can lead the play situation in these types of activities and note the ability of the child to engage in the “play” at a different level. The purpose is then presented clearly for the child, both for the language and for the movement, and thus becomes an active part of their developmental growth and understanding. Sometimes showing them or asking them to change their approach results in a larger perspective of possibilities in play. The examiner is an active participant in the assessment approach, engaged with the child in the semi-directed play type of assessment. The examiner notes closely when a child shows a lack of understanding of the language presented or an inability to make the movements requested. At all times the examiner is assessing how well the child appears to follow the purpose of the activity or the change in direction of an activity.”

Sources

- The Late Talker book Lisa Geng, Marilyn Agin MD, Malcolm Nicholl, St. Martin’s Press NYC NY https://www.amazon.com/Late-Talker-What-Child-Talking/dp/0312309244

- Dealing with an IEP for a speech impaired child https://pursuitofresearch.org/2011/10/12/dealing-with-ieps-for-a-speech-impaired-child

- Growing up with apraxia http://breaktheparentingmold.com/growing-up-with-apraxia/

- A Guide to Child Nonverbal IQ Measures Pennsylvania State University http://courses.washington.edu/sop/GuidetoChildNonverbalIQMeasures.pdf

Great information. Definitely passing it along. Thanks for taking the time to research this and share it with others.